Meghan Collins Sullivan/NPR

Meghan Collins Sullivan/NPR

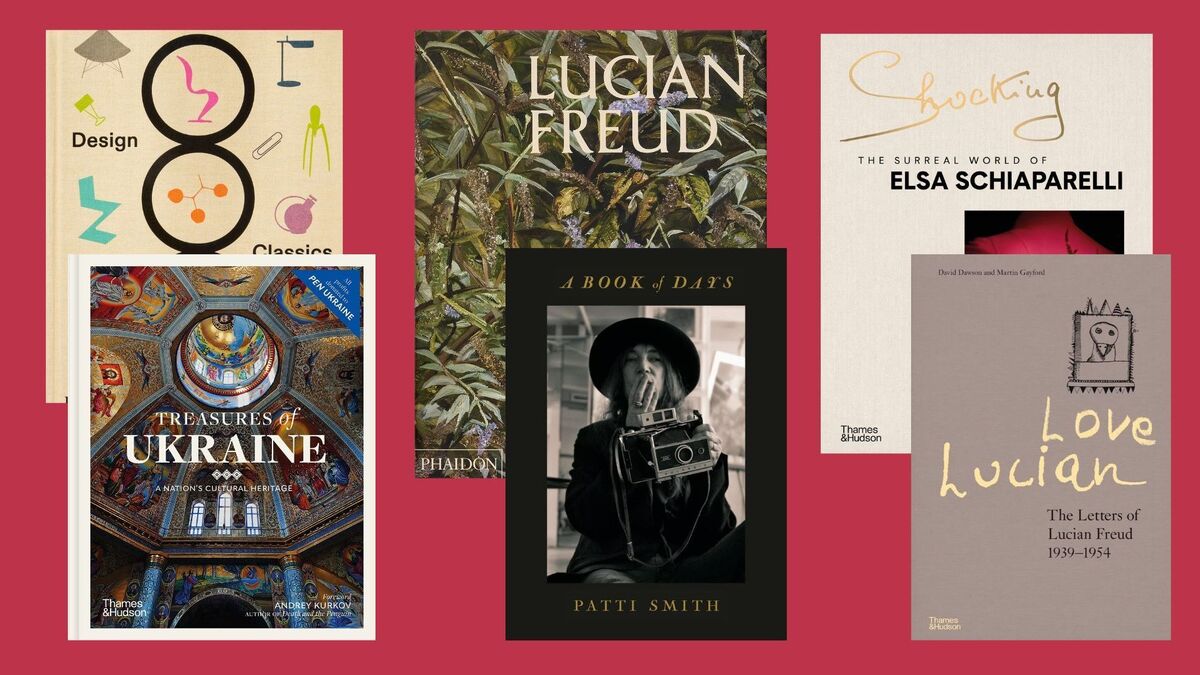

This year’s selection of visual delights highlights the work of artists and designers who have made an enduring impact.

Painter Lucian Freud’s centenary is commemorated with a sumptuous retrospective, plus a complementary volume that features his often playfully illustrated personal correspondence. A book about fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli explores how her avant-garde designs, often in collaboration with Surrealist artists, continue to wield influence and make waves, while a huge compendium of design classics showcases beautiful and innovative tools for living, from hairpins and wooden spoons to Eames chairs and Porsches. On a smaller scale, a yearbook of 366 snapshots by Patti Smith focuses on what has mattered most in her life.

And, last but not least, Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is the subject of a compact survey, which reminds us that there is so much more than grain and oil at stake in the country’s ongoing war for sovereignty.

Lucian Freud

The award for most eye-popping — and back-breaking — coffee table book of the year goes to Lucian Freud, a career retrospective of the British painter who died in 2011. Published in time to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth, it vividly captures what Martin Gayford, a longtime interpreter of Freud’s work, calls “one of the great marathon performances of art history.”

This massive, large format volume feels particularly apt for Freud’s famously corpulent nudes of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley (a.k.a. the Benefits Supervisor). There’s also plenty of space for his unflinching sequential studies of his mother aging over nearly two decades, his controversial nudes of some of his 14 children, and his many portraits of people with their pets, including his first wife, Kitty Garman, cuddling — yes — a kitty.

Freud’s work is never boring, though his aesthetic is not for everyone. Gayford points out in his introduction that “Truth, not beauty, was the star he steered by.” A lifelong champion of “naturalistic painting done from life,” he was a such a painstakingly slow worker that sitting for him was a grueling months-long commitment that demanded incredible fortitude and patience.

This book — some 480 full-color reproductions organized chronologically — contains treasures and surprises in each period, including landscapes and animals you wouldn’t necessarily associate with Freud.

The self-portraits alone tell quite a story, beginning with a broad-faced, dark-haired lad at age 17 in 1939. His body turns more sinewy and his face craggier through the decades, but the paintings still retain their ability to snag our attention — including the 1993 full frontal portrait of the artist working in the buff, padding around his studio in laceless boots.

A late self-portrait, “The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer,” offers a graphic depiction of both Freud’s hold on women and his priorities, a man whose focus on his art eclipsed everything else in his life. It captures a supplicant, naked young woman clinging to the artist’s pants leg, trying to distract him from his work in his paint-splattered studio lined with a bank of crumpled white rags. Poor girl.

Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud 1939-1954

If you’re hungry for more about Freud, Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud 1939-1954 offers an inviting portrait of the artist as a young man through facsimiles of his handwritten, often lavishly embellished personal correspondence.

Although not a biography, this richly illustrated and annotated book provides background, period photographs and reproductions of the artist’s portraits of his correspondents — including his first two wives, Kitty Garman and Caroline Blackwood, and his friend from his art school days, poet Stephen Spender.

Particularly fascinating is a letter to his grandparents, Sigmund and Martha Freud, meticulously and colorfully penned in German in 1932, when he was 10, thanking them for their gift of 15 Deutschmarks and some T-shirts. Another letter, also in German, to his father in 1939, ends with: “Air Raid Warning: PLEASE SEND ME MONEY.”

Shocking: The Surreal World of Elsa Schiaparelli

Shocking: The Surreal World of Elsa Schiaparelli is an alluring tribute to the inventive designer who was so far ahead of her time she’s still avant-garde nearly 50 years after her death. Born in 1890 to an erudite, aristocratic Italian family, she created her eponymous fashion house in Paris in 1927, and made her mark with eccentric, playful, and often Surrealist trompe-l’oeil designs. Her stylistic innovations included user-friendly wraparound dresses, culottes, and mix-and-match separates, while collaborations with artists like Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau blurred the line between clothing and art.

Shocking includes trenchant essays on Schiaparelli’s life, achievements, and influence, but it’s the photographs and images — like the pink gloves with black leather fingernails and the black gloves with pink patch nails from 1937 juxtaposed with Man Ray’s 1935 black-and-white photograph, “Hands Painted by Pablo Picasso” — that will grab your attention.

Particularly alluring is a 1938 photograph of Helena Rubinstein wearing a baby pink, short-sleeved bolero jacket embroidered with a network of acrobats suspended from a criss-crossed chain of what look like mice, and a ring of dancing circus elephants encircling its cropped waist. And then there are Schiaparelli’s signature lopsided, porkpie, pointed, knotted and dotty hats — surely inspiration for Dr. Seuss and Maira Kalman. Fabulous.

1000 Design Classics

For hours of happy browsing, it’s hard to top Phaidon’s 1000 Design Classics, an updated edition of their original three-volume visual history. This chronological collection of iconic chairs, light fixtures, cars, toys, tools, timepieces, tableware, telephones, and technology — which date from 1663 to the present — feels as if MoMA’s design gallery has been expanded to fill an IKEA store.

Many of these objects are such a part of our daily lives that we rarely stop to think about who created them — like the scissors designed by Zhang Xiaoquan in 17th century China; the safety pin, designed by New Yorker Walter Hunt in 1849 because he was frustrated by flimsy, prickly straight pins; and the key-opening sardine can, which J. Osterhoudt created in 1866.

It’s not just the visuals that make this book so compelling: The accompanying brief histories supply fascinating context. Ever wonder about all those ruffle-edged metal caps keeping the fizz in your soda? In 1891, an American named William Painter created the reliably leakproof, airtight cap to seal beer bottles. It was called the Crown Cap because that’s what it looked like when inverted. During Prohibition, Painter’s company switched to soft drinks in order to stay afloat.

In fact, an astounding number of items featured in this book are still in wide use — including playing jacks, Moleskine notebooks, clothespins, and Thonet chairs, which all date from the 1850s.

Other designs that have passed the test of time include Swiss Army knives (1891); paperclips (1899); the elegant Zeroll ice cream scoop, with its patented antifreeze-filled handle, created by Sherman L. Kelly in 1935; and Lego modular interlocking building bricks, whose 1958 injected-molded plastic design by Godtfred Kirk Christiansen evolved from his father’s earlier wooden toy blocks. (The name Lego is from the Danish, “leg godt,” meaning “play well.”)

The book is filled with hundreds of items still in production, including many in modified form — such as the Kitchenaid mixer first introduced in 1937 and, of course, the iPhone, born in 2007. As for items that are no longer produced — sports cars and racing boats, in particular — many have become coveted collectibles. Time will tell whether more recent designs, such as Iranian-French designer India Mahdavi’s Charlotte Armchair (2014), named for the dessert it resembles — Charlotte Russe — will endure.

A Book of Days

Appealingly compact and personal, Patti Smith’s A Book of Days is a curated collection of 366 photographs arranged to span a calendar year. This mix of Polaroids from her now-retired Land camera and cellphone snapshots, which she began posting on her popular Instagram account (thisispattismith) in 2018, provide a window into what matters to the writer and performer.

The overall mood is contemplative and nostalgic. The caption beneath an old pay phone captures the tone: “With heaven’s dime I would call time past.”

The book is filled with memories and associations, often tied to specific dates. Smith marks the birthdays of dozens of friends, loved ones, and people she admires with poignant tributes. Many are no longer with us — including her husband, Fred Sonic Smith, her former lover, Robert Mapplethorpe, and her former lover and friend, Sam Shepard — and his literary hero, Samuel Beckett. But she also salutes many who are still alive, including her two children, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Yoko Ono.

We learn a lot about Smith by what she chooses to include. A favorite book from childhood, Around the World in 1,000 Pictures, helped inspire her lifelong wanderlust.

Among the memorabilia pictured: her mother’s key ring, her father’s coffee cup, and “an image of pure happiness” — Smith on her first bicycle in 1951. Mapplethorpe, the subject of Just Kids, her 2010 National Book Award-winning memoir, is well-represented by several talismans, including a Valentine’s Day card from 1968 and the striking photograph he took of Smith for her Horses album cover in 1975. One surprising memento is a traditional string of pearls — a 40th birthday gift from her husband.

Smith likes to visit the farflung gravesites of her literary touchstones, including James Joyce in Zurich, Susan Sontag in Paris’ Montparnasse Cemetery, and William S. Burroughs, whose modest headstone in St. Louis is dwarfed by the imposing monument to his grandfather, also William S. Burroughs, inventor of the adding machine.

She also has a penchant for photographing more temporary resting places — the spartan beds of famous artists — including her own in Rockaway, New York.

A Book of Days adds up to an oblique but moving memoir by an artist whose response to her own losses is encapsulated in her comment commemorating 9/11: “We bend to remember the departed, then rise to embrace the living.”

Treasures of Ukraine: A Nation’s Cultural Heritage

Treasures of Ukraine, a brief overview of Ukraine’s rich cultural history from prehistoric times through the present, is a timely reminder of how much is at stake in the ongoing war with Russia. In the 30-plus years since the country’s independence following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has revived its language and embraced its history and culture after decades of enforced Russification.

Although readers will be most familiar with the traditional folk art textiles embroidered with geometric ornamental motifs and the gorgeous, elaborately hand-decorated pysanky Easter eggs and earthenware bowls, this book features a broad range of Ukrainian art.

For centuries, decorative clay pots and jugs were fabricated by peasants not just for personal use, but in exchange for food, or as tributes for their landowners. Beautiful beige and green ceramic stove tiles were produced in the west Ukraine city of Kosiv, its largest center of arts and crafts.

Much of Ukraine’s art is tied to religion — including cathedrals and Byzantine icons, whose aesthetic was connected with its eastern Christian inheritance. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Christian imagery was infused with folk art in carved wooden figurines.

But as this book shows, Ukraine is no stranger to Modernism, Art Nouveau or the Avant-garde. The monumental, early 20th century murals of Mikhailo Boichuk and his followers, the Boichukists — including propaganda commissioned by the then-new Bolshevik regime — are oddly evocative of WPA projects in the U.S.