Edward Wong and Ana Swanson reported on the front page of today’s New York Times that, “Hulking ships carrying Ukrainian wheat and other grains are backed up along the Bosporus here in Istanbul as they await inspections before moving on to ports around the world.

“The number of ships sailing through this narrow strait, which connects Black Sea ports to wider waters, plummeted when Russia invaded Ukraine 10 months ago and imposed a naval blockade. Under diplomatic pressure, Moscow has begun allowing some vessels to pass, but it continues to restrict most shipments from Ukraine, which together with Russia once exported a quarter of the world’s wheat.

“And at the few Ukrainian ports that are operational, Russia’s missile and drone attacks on Ukraine’s energy grid periodically cripple the grain terminals where wheat and corn are loaded onto ships.

An enduring global food crisis has become one of the farthest-reaching consequences of Russia’s war, contributing to widespread starvation, poverty and premature deaths.

Wong and Swanson explained that, “The United Nations World Food Program estimates that more than 345 million people are suffering from or at risk of acute food insecurity, more than double the number from 2019.

“‘We’re dealing now with a massive food insecurity crisis‘ Antony J. Blinken, the U.S. secretary of state, said last month at a summit with African leaders in Washington. ‘It’s the product of a lot of things, as we all know,’ he said, ‘including Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.’

“The food shortages and high prices are causing intense pain across Africa, Asia and the Americas. U.S. officials are especially worried about Afghanistan and Yemen, which have been ravaged by war. Egypt, Lebanon and other big food-importing nations are finding it difficult to pay their debts and other expenses because costs have surged. Even in wealthy countries like the United States and Britain, soaring inflation driven in part by the war’s disruptions has left poorer people without enough to eat.”

The Times article noted that, “From March to November, Ukraine exported an average of 3.5 million metric tons of grains and oilseeds per month, a steep drop from the five million to seven million metric tons per month it exported before the war began in February, according to data from the country’s Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food.

“That number would be even lower if not for an agreement forged in July by the United Nations, Turkey, Russia and Ukraine, called the Black Sea Grain Initiative, in which Russia agreed to allow exports from three Ukrainian seaports.

“Russia continues to block seven of the 13 ports used by Ukraine. (Ukraine has 18 ports, but five are in Crimea, which Russia seized in 2014.) Besides the three on the Black Sea, three on the Danube are operational.”

Today’s article also pointed out that, “The United States, Brazil and Argentina, key grain producers for the world, have experienced three consecutive years of drought. The level of the Mississippi River fell so much that the barges that carry American grain to ports were temporarily grounded.

“The weakening of many foreign currencies against the U.S. dollar has also forced some countries to buy less food on the international market than in years past.”

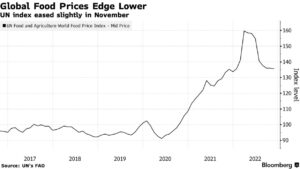

Wong and Swanson indicated that, “Over the last six months, food prices have retreated from highs reached this spring, according to an index compiled by the United Nations. But they remain much higher than in previous years.

“An uncertainty for farmers this winter is the soaring price of fertilizer, one of their biggest costs.”

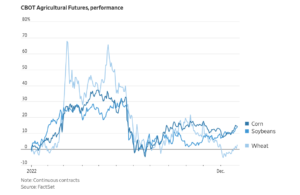

Meanwhile, Kirk Maltais reported today at The Wall Street Journal Online that, “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent U.S. grain futures soaring early in 2022 before their recent retreat. The new year promises to be another volatile one.

“Futures for wheat and soybeans reached record highs earlier in 2022, and corn futures notched their highest level in more than a decade. The war stifled supply, and so did dry weather in many crop-growing areas.

“Now, grain prices have fallen close to where they started 2022. The decline tracks with an overall easing of prices for commodities from natural gas to cotton and lumber, which have slipped in recent months after surging. More interest-rate boosts by the Federal Reserve and other central banks to cool economies—a process many analysts say could result in at least a modest recession in 2023—are expected to keep a lid on demand.”

The Journal article noted that, “‘The wild card for grains is the Russia-Ukraine shipping deal and its survivability,’ said commodities analyst Jim Wyckoff. ‘It’s a shaky situation that grain traders will continue to monitor very closely.’”

“Grain futures shot up to historic levels in the early days of the Russia-Ukraine war. Most-active wheat futures trading on the Chicago Board of Trade rose to a record high of $12.94 per bushel in March, beating the previous high set in 2008. Soybean futures also found their record high, rising to $17.69 per bushel in June. Corn futures climbed to $8.14 per bushel in April, the highest they have been since 2012.”

Maltais added that, “China, the world’s leading grain consumer, also will affect the outlook for agricultural futures in 2023. The country recently said it would rescind its strict measures to control the spread of Covid-19.

“‘China should see a period of significant economic growth in 2023, but that is expected to be capped in the first half of the year by rapidly spreading Covid,’ said Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist with StoneX Group.”